City played a role in Old West cattle drives

Becoming part of the U.S. offered Texas ranchers more markets.

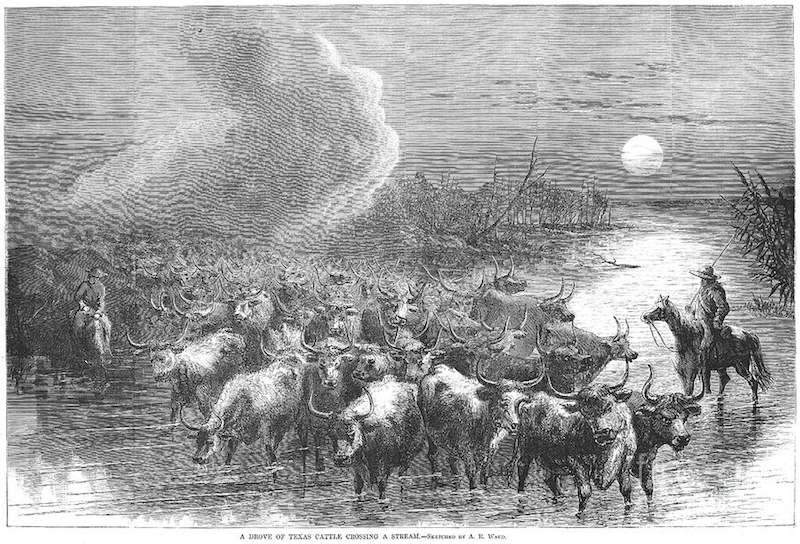

Actors like John Wayne and Gary Cooper made the legends of cowboy’s part of American folklore. Many Americans know about the Chisholm and the Loving-Goodnight trails -- routes Texas cowboys followed to drive vast herds of cattle north to railroads and markets in Kansas after the Civil War. On a webpage titled "Cattle Folk 1850-1880s," the Bullock Texas State History Museum said, "From the 1860s to the late 1880s, cowboys herded over ten million cattle to market on the controlled chaos of a trail drive."

For a brief time before that era, Quincy had a role in the cattle drives of the Old West. Probably fewer have heard of the Osage Trail, which ran between Texas and St. Louis, or the Shawnee Trail, which had one terminus in Quincy.

Lyndon Irwin wrote on the Missouri State University Agriculture History Series website: "Many Texas cattle came into Missouri by way of the Shawnee trail which crossed into Missouri's borders between 1850-1900. Generally these cattle crossed where Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma meet. From this point three main trails were taken to the railheads at St. Louis, Sedalia, Quincy Illinois and Kansas City."

When Texas achieved statehood in 1845, it had already been producing beef cattle for several centuries. Becoming part of the U.S. offered Texas ranchers more markets. The first trail drives were to New Orleans. The Gold Rush of 1849 took thousands of fortune seekers to California, and soon cattle drives also went from Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas to the West Coast.

The coming of railroads in the 1850s changed the way cattle got to market, but Missouri was a key state in the cattle drives, both before and after the railroads came. The Shawnee Trail, which the Texans called the "Texas Road," followed the border between Missouri and Kansas north to Kansas City and Independence. In 1854 alone, an estimated 50,000 longhorns were driven north from Texas.

Illinois had a different role from Missouri in getting the cattle to market. Some herds were driven across the Mississippi at St. Louis, then pastured and fattened in Illinois before being driven or taken to Eastern markets. Most cattle drives consisted of several thousand animals, but a few herds were small.

Two unrelated factors pushed the trail riders farther east and west, away from the western Missouri routes: tick fever and slavery. The first of those, tick fever, also called Texas fever, broke out in the cattle herds of western and central Missouri in 1855, killing thousands of animals, and Missouri farmers blamed it on the Texas herds being driven across the state. They formed vigilante committees to stop the Texas herds, and petitioned the state legislature to back them up.

The Legislature took action. Its lawmakers assumed that the Texas cattle were sick, and passed a quarantine law that went into effect Dec. 15, 1855. Local justices of the peace were empowered to charge a penalty of $20 for each diseased Texas animal they found, but Texas cattle had built up immunity to the ticks and rarely got the sickness, so the law was seldom enforced. Even so, cowboys could avoid the western vigilantes altogether by driving the herds farther east to St. Louis or Quincy on those branches of the Shawnee Trail.

The second factor that made cattle drives to Quincy and other locations east of Kansas and Missouri safer than the western trails was the growing turmoil over slavery. When the Kansas Territory opened for settlement in 1854, thousands of pro-slavery Missourians and anti-slavery Easterners (nicknamed Free-Soilers) flooded in, anticipating the vote that would determine whether Kansas became a slave or a free state, and armed conflict broke out that lasted several years. That ongoing violence added another serious risk to cattle drives from Texas.

Herd owners opted for other markets with safer routes, particularly in rapidly growing California, and for a few years, few crossed Missouri and Illinois. In 1856 one herd made it from Texas to Chicago; in 1857, two got to Quincy; and in 1858, one came to Hannibal, Mo.

After 1859, when the railroad was completed all of the way across northern Missouri from Hannibal to St. Joseph, then later into Kansas, herds were driven directly north from Texas to the numerous "cow towns" that sprang up along the tracks, and most of the cattle were taken to markets by train. No more records were found of any Texas drives that reached Quincy.

The claim to being the last cattle drive in Quincy did not involve Texas cattle. Arthur E. Bowles recounted in "Tales from Two Rivers I" that in the 1920s, Quincy freight companies and private citizens owned hundreds of horses and cattle and required large quantities of hay, corn, and oats to feed them. His father was a hay farmer, and Bowles had heavy responsibilities from a young age, hauling hay to the city market at Ninth and Hampshire. He acquired riding skills and the ability to handle livestock when still a boy.

Bowles recalled the time that a cattle buyer bought stock in several townships and hired him and several other young men to round up all of the animals at Spring Lake Corners. From there, they were to drive the newly formed herd south on 12th Street to the stockyards, just west of the present location of Blessing Hospital.

Bowles recounted: "We had quite a drive.... Ever (sic) so often one would bolt (with a little urging from us boys so we could show off our horsemanship and cowboy tactics).... If there were any girls in sight, we would give a war whoop to add a little color to our fancy riding. I think some of the younger cattle got into the spirit of the thing with us.... We got them into the stock yards and never lost a head to rustlers or Indians."

That's quite a legacy for one of Quincy's last cowboys.

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing, and serves on the board of the Historical Society.

By LINDA RIGGS MAYFIELD

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing, and serves on the board of the Historical Society.